Buying a Used Electric Car? Here’s Everything You Need to Know

Contents

- Is an EV Right for You?

- The Used EV Marketplace

- Benefits of EV Ownership

- Lower Running Costs

- Fewer Miles, More Features

- The Feel Good Factor

- EV vs. PHEV

- Battery Basics

- How Long do EV Batteries Last?

- Replacement Costs

- Used EV Values

- Your Actual Range May Vary

- EV Charging

- Charging Away from Home

- Forget Gallons, with EVs it’s Kilowatts

- How Much Does it Cost to Charge an EV?

- Taking an EV for a Test Drive

- The Bottom Line

Electric cars — whether battery-electric EVs with no gas engine at all, or plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) that combine electric drive and internal combustion engines — are still a mystery to most Americans.

Even in California, which has been pushing them as a matter of state policy for nearly a decade now, fewer than half the respondents in survey after survey acknowledge knowing much about these cars.

Top of the “things-to-know” list is that, unless something’s gone horribly wrong with the battery (and that’s quite rare), a used electric vehicle can represent one of the best used car deals in the market today.

That’s because EVs are usually loaded with features that can be pricey options on cars with conventional gas or diesel powertrains. They typically also have far fewer miles on their odometers, and they deliver significant savings in both fuel and maintenance costs compared to cars with internal combustion engines.

And in most cases, depreciation rates for EVs are higher than for their conventionally-powered counterparts, which means that their prices, tempered by consumer wariness of the still-unfamiliar technology, are relative bargains.

Is an EV Right for You?

It’s true that cars with plugs aren’t for everyone or every lifestyle.

On the plus side, thanks to their powerful electric drive systems, they can be fun to drive and inexpensive to maintain, and they make great commuters or grocery getters. In addition, both pure EVs and plug-in hybrids can offer a step up in power and features, often at a lower overall cost than conventionally powered models. People who drive EVs usually fall in love with these perks. But there are circumstances where EVs don’t always make sense.

Top of mind for most potential EV shoppers is range. Pure EVs, of course, have range limitations that can limit their usefulness for some purposes, such as long-distance travel. So if you regularly drive more than 300 miles in a day, an EV is probably not the car for you.

While plug-in hybrids don’t have any range limits that a stop at a gas station can’t resolve, their owners still need to fill the gas tank once in a while, even while plugging-in every night to charge the electric drive system’s battery. And because they still have gas engines, PHEVs also continue to emit planet-warming CO2 along with toxic and smog-causing gasses, although in considerably less quantity than the typical gas-only car or truck.

Another consideration: both types of EVs also require home charging systems — typically a $500 to $1,500 cost to purchase and install — to operate at their highest efficiency.

The Used EV Marketplace

Quantity helps make a market more competitive and keep prices down. In the case of used plug-in vehicles, the market is just starting to blossom.

A total of just 1.44 million new EVs and PHEVs were sold in the U.S. from 2011 through the end of 2019. By comparison, about 5.4 million standard hybrids and 139.5 million conventionally-powered light cars and trucks were sold during the same nine-year stretch. That’s just one EV or PHEV for every 100 conventional gas, diesel, or standard hybrid cars and trucks. And most of those plug-ins were sold in just a dozen states, a list topped by California, which accounts for about 25 percent of all EV sales.

Still, there are several thousand 2011-2017 EV and PHEV models, many of them lease returns and trade-ins, being offered for sale in the current market by dealers and private parties. A review of several hundred of these listings shows that most three- and four-year-old models are selling through dealerships for 50 percent or less of their original MSRPs, while private-party sales prices are typically a few points lower.

Teslas are an exception, with most three-year-old Model S sedans offered at about 40 percent off their original price, or roughly the same as the average depreciation for a conventionally-powered car, and Model X crossovers at an average 35 percent reduction.

Most of the used vehicles available today are sedans or small hatchbacks. Larger crossover EVs and PHEVs have only recently appeared, so only a few models have been around long enough to trickle down into the secondhand market.

And so far there are no electric or plug-in hybrid pickups, although new models are being developed by both mainstream companies like Ford and GM and by newcomers such as Rivian and Bollinger. It likely will be 2025 or after before there’s a meaningful supply of used electrified pickups.

One other factor that limits variety for used EV shoppers is that many models are sold only in a handful of states that actively promote EV and plug-in hybrid use. That means EVs such as the Ford Focus EV, Fiat 500e, Hyundai Ioniq EV, and Volkswagen e-Golf aren’t available in every state.

Benefits of EV Ownership

Lower Running Costs

EVs offer drastically lower costs for upkeep than conventionally-powered cars. As labor prices climb and cars get more and more sophisticated, it can now cost hundreds of dollars just to replace spark plugs in an internal combustion engine. But EVs have no plugs. Also absent under an EV’s hood: oil, fan belts, fuel pumps, water pumps, and of hundreds of other moving parts that an internal combustion engine requires.

In fact, their electric motors are sealed units with just two or three moving parts and virtually no maintenance requirements, so you’ll only need to visit the shop for things like periodic tire rotations and windshield wiper and cabin air filter replacements — and for cars with liquid-cooled battery packs, a coolant change once every five years or so.

EV “transmissions” also are much simpler than a typical gearbox. Since an electric motor’s torque is instantly available, it provides all the power necessary to get the vehicle moving and to keep it traveling at speed without needing move through a series of gear ratios.

Ford once estimated that a Focus EV would save $120 a year in ongoing maintenance costs versus a conventionally powered Focus. That’s a cool $1,200 over a 100,000-mile, 10-year lifetime.

Plug-in hybrids are a bit less thrifty because they still have an internal combustion engine to maintain. But wear and tear on the engines typically is reduced because they are frequently augmented by the electric motor and don’t have to work as hard.

There also are big savings on brake maintenance. Both types of plug-ins have regenerative braking systems that capture energy released as the vehicle slows down. The systems use the electric motor rather than the conventional brakes to do most of the work and are dialed-in to recuperate as much juice as possible to replenish the battery pack. As a result, regenerative braking in plug-in cars is so good at slowing things down that in most cases the conventional brakes are only used in the final moments of coming to a stop, meaning that many plug-ins can run for 100,000 miles or more before needing a brake job.

Fewer Miles, More Features

Because an EV’s range is limited, most three- or four-year-old models have half the miles on their odometers that similar gasoline or diesel powered cars of the same vintage typically have.

Plug-in hybrids don’t have range limits so often come with higher mileage, but they also deliver two to three times the fuel efficiency of hybrid and conventional models.

In fuel costs alone, a 2016 Chevrolet Volt PHEV can save an average of $800 a year versus a 2016 Chevy Cruze, per federal Environmental Protection Agency efficiency ratings. Fuel savings hit $1,000 a year in the all-electric 2016 Chevy Bolt versus the Cruze.

Another big plus is that most EV models are outfitted when new with loads of upscale features and infotainment technologies, which are aimed at attracting wealthier buyers who can afford the higher cost of a plug-in powertrain (when new). And as with conventionally-powered cars, those features don’t always hold much value in the secondhand market, so buying a used EV usually means getting perks like leather, navigation, full-range cruise control, even self-parking technology without paying any extra.

The Feel Good Factor

Many EVs were sold initially to people who sought them out at least in part to support their desire to help the environment by reducing their carbon footprints. That may not be as big a driver in the used market, where price is typically the top concern, but buying a used EV or PHEV still does have a positive environmental impact.

Even when their juice comes from coal-fired powerplants, electric vehicles are so much more efficient than internal combustion cars in turning that electricity into propulsion power that the end result is a cleaner “well-to-wheels” profile for EVs.

If you’d like to see the numbers for yourself, check out this local emissions calculator, provided by the Union of Concerned Scientists, which lets you see, on a ZIP code level, how any particular EV or PHEV stacks up against any gasoline-only model.

EV vs. PHEV

EVs, or battery-electric vehicles, have no gas engine and are entirely dependent on their batteries for power. Therefore owning one requires a willingness to plan longer trips carefully and to be methodical about plugging-in to keep that battery charged and ready to go.

Also, most EVs available on the used market are considered first generation models (introduced from the end of 2010 until around 2017), and their range is more limited than the newest models hitting showrooms today. That means most provide under 120 miles of range — and some under 100 miles.

An older EV’s limited range really isn’t a problem for most people, though. The average American commute is 16 miles each way, or 32 miles round trip, which is well within the range of most used EVs. And for those with a longer commute, many employers provide charging stations in the parking lot at work. It’s the rare driver who travels more than 60 miles a day to get to and from school or work or to do the daily shopping.

And should you run low on juice unexpectedly or want to travel longer distances, there’s a sizable and fast-growing public network of highway-oriented, high-powered “Level 3” quick-charge stations that can top up an EV’s batteries in the time it takes to eat a quick lunch or take a restroom and coffee break.

A plug-in hybrid, on the other hand, pairs its electric drive system to an internal combustion engine, so you can jump in and drive all day without worrying about finding a charging station. The gas engine kicks in as soon as the battery packs start to become depleted. A 2016 Chevrolet Volt, for instance, will go about 50 miles on a fully-charged battery, then an additional 360 miles running in gas-electric mode, with its small 4-cylinder engine generating power to drive the electric motor. If you want to push past 410 miles, all you have to do is stop at a gas station and refill the 8.9-gallon tank with premium, and you are good for another 360 miles or so without having to find a charging station.

All-electric range among used PHEVs varies from a low of just 11 miles for the Mercedes Benz C350e sedan, introduced in 2015, to a high of 53 miles for the Chevrolet Volt, introduced in 2011. If you have a relatively short daily commute, you might even be able to run your PHEV all week on electricity, using gasoline only on longer trips.

While PHEVs aren’t constrained by battery dependence and range limits, they have a few other drawbacks of their own. First, unlike a pure EV, with a PHEV you still have to maintain the internal combustion engine, change the oil regularly, stop at gas stations from time to time, and (perhaps) apologize to the planet once in a while for your tailpipe emissions.

As for EVs, the big potential negatives are that their range declines as the batteries age and deteriorate, and that battery replacement, if needed during your ownership, can be a fairly expensive proposition.

Battery Basics

How Long do EV Batteries Last?

Battery life is the 800-pound gorilla in the EV world. There’s a lot of hand wringing about the issue; however, so far, concerns about battery life in EVs seem to be overblown.

First of all, few of the vehicles have been around long enough to exceed their initial battery warrantees, which are typically 8 years or 100,000 miles. As a rule of thumb, though, battery engineers expect EV batteries to last well beyond their warranty periods. Liquid-cooled systems such as those used by Tesla, Jaguar, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volvo, and General Motors are showing greater long-term dependability than air-cooled systems used by Nissan and by Ford in the recently discontinued Fusion and C-Max Energi PHEVs.

The lithium-metal chemistries for EV batteries that automakers started with and still use today are fairly robust. A recent study of 6,300 EVs showed that the average annual capacity loss was just under 2.5 percent. Most still had 80 percent of their original battery capacity – and range – after eight years. So an EV with 100 miles of range when new should have at least 92 miles of range at age three and 80 miles after eight years on the road. There are Tesla taxis on the road right now, though, with close to 500,000 miles on their original batteries and Tesla CEO Elon Musk is promising a million-mile battery pack in the near future.

Replacement Costs

In the unusual case where a replacement battery is needed outside the factory warranty period, the cost can be significant, especially for pure EVs. For instance, a 26-kWh battery pack replacement for a Nissan Leaf runs about $6,000-$8,000 (plus installation), and an 85-kWh Tesla battery will put a $10,000-$14,000 hole in your wallet.

Since PHEV battery packs are much smaller, they tend to cost less than EV batteries, but they still are pricey because of the cost of the associated safety packaging and electronics. A replacement 7.6- kWh battery for a 2017 Ford C-Max Energi can run almost as much as the much-larger battery for a Nissan Leaf.

Prices are expected to fall considerably over the next five years, however, so by the time most EVs need new batteries, the replacement costs should become more manageable — especially as aftermarket replacement options become available. That is the case currently for conventional hybrids but not for EVs yet because so far there’s not sufficient demand.

Also of note, California recently approved development of a program, expected to launch in 2021, to provide financial assistance to purchasers of used plug-in-vehicles who face the need to replace an EV or PHEV battery, a program could potentially be adopted by additional states in the future.

Almost all EV and PHEV batteries have at least an 8-year or 100,000-mile warranty. And in the so-called ZEV states that have adopted California’s zero-emission vehicle rules, PHEVs have even longer battery warrantees (10 years or 150,000-miles). That’s because their batteries are considered a key part of the states’ emissions reduction systems. (The rationale is that an EV can’t run at all when its batteries dies, but a PHEV with a dying battery can run on its gas engine alone, producing higher levels of tailpipe emissions than it would if that engine were still being assisted by the battery-electric powertrain.)

Used EV Values

As noted earlier, the values of EVs tend to drop even more significantly than conventionally-powered models after they drive off the new car lot, in part because their original MSRPs were deflated by federal and state incentives. There also has been downward pressure on prices due to buyers’ fear (largely unwarranted) about EV battery life and replacement costs.

However, that trend is changing. “Consumers are more confident now,” says Ivan Drury, Senior Manager for Industry Analysis at Edmunds.com. EVs “still aren’t holding their value like conventional powertrains, but they aren’t losing like they used to,” he notes.

They can still be great bargains, though. “The 2016 Fiat 500e is only holding about 29 percent of its original value,” Drury said of Fiat’s 84-mile EV, which was sold only in California and Oregon. While the 2019 Fiat 500e is listed at $27,705 after a $7,250 manufacturer’s rebate, it is relatively easy to find a 2016 500e with the same range, equipment and body styling in the $8,000-$10,000 range, and with fewer than 36,000 miles on the odometer.

And as second generation EVs (with 200+ miles of range) enter the used market, depreciation is even less significant, say Eric Ibarra, Director of Residual Value Consulting at KBB (formerly Kelley Blue Book). For instance, the Chevrolet Bolt, with 238 miles of range, has greater value retention (the used price as a percentage of new-car MSRP) than a similarly-equipped Chevrolet Cruz, he points out. The same is true of the second-generation Nissan Leaf, which comes in 150-mile and 226-mile versions, versus a similarly sized and equipped gas-only Nissan Sentra.

Based on this analysis, bargain hunters should target first-generation EV models, while shoppers who value longer ranges should consider paying the small premium for a second-gen car.

Your Actual Range May Vary

The distance an electric car can go on a battery full of electrons is a lot more susceptible to external conditions and driving styles than is the range of a car with an internal combustion engine and a tank full of gas. Your speed, how hard you brake, how quickly you accelerate, the terrain you’re driving over, how much cargo you carry (including passengers), even the weather, all impact range.

For instance, an EV rated at 85 miles of range per charge may only give you 70 to 77 miles if you do the entire trip on the freeway at 70 miles per hour. Climbing hills drains batteries faster than coasting down can replenish them. Hard braking applies the mechanical brakes sooner and reduces the amount of regenerative braking that helps top up the battery charge. It takes energy to move weight, so as the cargo and passenger loads increase, some of the energy ordinarily devoted to covering distance is diverted to help get the extra weight into motion.

Range also falls in extreme heat and cold, which has to do with how temperature affects a battery’s capacity to take a charge and discharge its electrons. A range test by the American Automobile Association found that an EV that traveled 105 miles in 75-degree weather delivered only 57 miles when the temperature was 20 degrees, and 69 miles at 95 degrees.

PHEVs have the same range constraints when operating in all-electric mode. But unlike pure EVs, of course, plug-in hybrids have gas engines that aren’t tethered by a charging cords.

Considering how far you need to drive each day, the kind of terrain you’ll be driving, the load you’ll be carrying, and the temperature ranges in which you’ll do most of your driving –- plus an honest self-assessment of your driving style –- will help you to avoid choosing an EV that disappoints.

EV Charging

Books have been written about it, but you don’t have to read one to understand the basics of EV charging. You will need to know a little bit, though, to make the best decisions when it comes to picking out a plug-in vehicle.

Most EV owners use home charging, plugging their cars in at night when they are not in use and when electricity rates are lowest. That enables them to start fresh each morning with a full battery (at the lowest cost).

While all EVs and PHEVs can be charged with standard 120-volt household current, or “Level 1” charging, it takes a long time — a full day or more for most EVs.

The standard for EV home charging is a 240-volt or “Level 2” system. Home charging stations can be purchased through new car dealerships or independently through charging system manufacturers and even from big-box stores such as Lowes and Home Depot.

When determining your charging needs, remember that Level 1 charging rarely adds more than 5 miles of range per hour, while Level 2 charging delivers juice at a rate equal to 10 to 25 miles of range per hour. The precise rate depends on the capacity of the car’s on-board charger and the charging station to which it is connected.

Charging Away from Home

Some employers have installed parking lot charging stations, so workplace charging can augment or even replace home charging for some. There also are public Level 2 stations in numerous retail locations and government facilities that can be used in a pinch.

When you are on the road, there are networks of publicly-available Level 2 chargers, usually clustered in major urban areas. There also are hundreds of Level 3 charging stations, called rapid or quick chargers, that EVs can use to quickly top up a battery for a bit of extra range while on road trips.

All EVs come either with a smart phone app or a standard or optional on-board navigation system that locates and provides directions to nearby public charging stations.

There also are regional and national networks, such as Blink, ChargePoint, Electrify America, EVgo and EV Solutions, that provide on-line and mobile phone directions and access to their stations.

Plugshare, a group-sourced network, has a free app that lists public charging stations from more than a dozen networks.

Forget Gallons, with EVs it’s Kilowatts

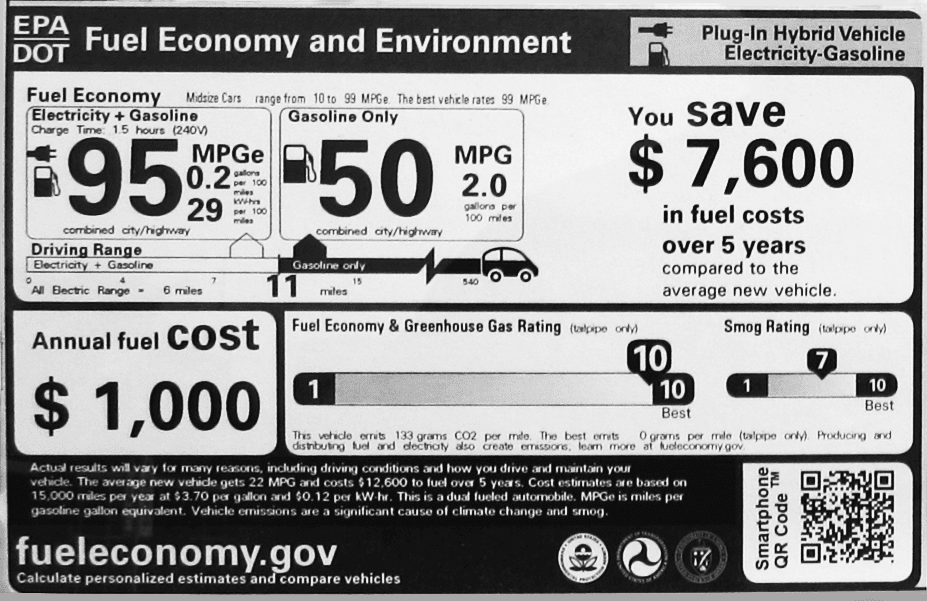

PHEV owners don’t have to worry much about the peculiarities of measuring fuel economy because their vehicles still have gas tanks. The central computer keeps track of battery-electric and internal combustion engine use and displays fuel efficiency as MPGe, or miles per gallon equivalent.

But for EV drivers, gallons are a thing of the past. Fuel efficiency is instead figured in miles per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of power consumed. That’s convenient because your home electricity bill is also based on kWhs.

What you need to know to make sense of it all is that 33.7 kWh of electricity is the energy equivalent of a gallon of gasoline. An EV with a 26-kWh battery pack is carrying the equivalent of 0.75 gallon of gas; a 7-kWh plug-in hybrid battery packs the equivalent of 0.2 gallon.

From a fuel economy perspective, driving an EV with a 26-kWh battery that delivers 100 miles of range is like driving standard car that gets 130 miles to the gallon.

How Much Does it Cost to Charge an EV?

Many utility districts have special discount rate plans for EV owners. Before you go car shopping, call your electric utility’s customer service line and ask for information about electric vehicle charging.

You should also look at your last year’s electricity bills to figure out your average cost of a kilowatt-hour of power. That can help you calculate how much charging that new EV would add to your bill before any special rate plan is applied.

At the national average of just under 13 cents per kWh, charging a 26-kWh battery would cost around $3.30.

If you drive 1,000 miles a month and average 85 miles per charge, the monthly cost before any special rate plans would be $38.80. With $2.50 per gallon gasoline, a conventional car getting 30 mpg would consume $83.33 worth of fuel for the same 1,000 miles.

Taking an EV for a Test Drive

As with any used vehicle, it’s important to take a test drive before buying a used electric car, especially if you’ve never driven one before. The EV driving experience can be quite a bit different from what you might be used to. For instance, electric cars don’t have engine noises to drown out typical road noise and interior creaks and rattles, so try rolling up the windows and turning off the radio and AC for part of your drive to see if you can live with these ambient noises.

Also, make sure you are comfortable with the brake action. Some drivers find regenerative braking systems difficult to get used to and complain that the car is too jerky or unresponsive when they are stopping. If you find this to be the case, then a used EV might not be a great fit for you.

If you are looking at plug-in hybrids, be aware that they automatically shift between gas and electric modes as the central computer maximizes fuel economy. They also have engine stop-start systems that shut down the gas engine at stoplights and when idling. The transition between gas and electric modes can be jerky in some models, while almost unnoticeable in others. You might need to try out a few different models to find the one which suits you best.

Finally, before you pull the trigger on a used EV, check the location of the charging port and the cord length just to make sure they can work with your home charging setup

The Bottom Line

Buying a used electric car is not for everyone. But if you’re looking for a great commuter or around-town car that’s both cheap to acquire and inexpensive to run, a used EV can be an excellent choice. Not only are they less costly than their conventionally-powered counterparts, they are also typically better equipped — not to mention better for environment. And with more and more EVs entering the used car marketplace, now is a better time than ever to find the right one for you.

Photos courtesy BMW, Chevrolet, Honda, Hyundai, Nissan, Tesla, Volkswagen, and Wikimedia Commons